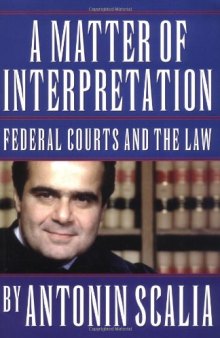

دانلود کتاب A matter of interpretation: federal courts and the law: an essay

by Antonin Scalia, Amy Gutmann|

|

عنوان فارسی: یک ماده از تفسیر: دادگاه های فدرال و قانون: یک مقاله |

دانلود کتاب

دانلود کتاب

جزییات کتاب

جزییات کتاب

The book is essentially a collection of essays and takes the form of a discourse between Scalia and four prominent colleagues: historian Gordon Wood and legal scholars Laurence Tribe, Mary Ann Glendon, and Ronald Dworkin. The book checks in at a breezy 159 pages, with 46 devoted to Scalia's main essay and another 12 as a response to the commentaries. The commentaries themselves average roughly 20 pages per author.

The crux of Scalia's essay is that judges who "interpret" statutory and constitutional texts on the basis of what they think the law ought to be, rather than on what it actually is, are usurping the legislature and undermining both our constitutional form of government and the famous American ideal that ours is "[a] government of laws, not of men." Unfortunately, such judges have come to predominate due to deficiencies in legal education and routinely distort or outright ignore legal texts in order to achieve the outcome they deem desirable from a policy standpoint. For extrinsic validation of Scalia's premise, one need look no further than Supreme Court nominee Sonya Sotomayor, who has repeatedly expressed the disconcerting view that the job of a judge is to make policy.

In response to this corrosive epidemic, Scalia points to textualism and originalism as the panaceas. Scalia's particular brand of textualism--the irreproachable philosophy that enacted law must be interpreted consistently with the text itself--is defined by the principle that texts should neither be interpreted strictly nor leniently, but "reasonably, to contain all that they fairly mean." Similarly, Scalia's form of originalism (original meaning, as opposed to original intent) holds that constitutional provisions should be interpreted according to what a reasonable person living at the time the provision was ratified would understand it to mean. Where textualism ties judicial interpretation to the text, original meaning ties interpretation of the text to the time period in which it was enacted. This makes an abundance of sense for a variety of reasons, namely because only the text IS the law, and only a temporally-fixed interpretation reflects the will of the legislative body that enacted the law and provides any real protection to the citizens living under it.

Having articulated his own jurisprudence, Scalia concludes with a scathing attack against the notion of a "Living Constitution," a philosophy antithetical to originalism that argues the Constitution can evolve and take on new meanings over time.

While Scalia's contributions are first-class, the comments leave much to be desired. Wood's essay is a bland historical overview of judicial lawmaking in America and fails to engage Scalia's ideas beyond suggesting the problem may go back longer than the Justice realizes. Glendon's note is a comparison between the interpretive skills of practitioners in the civil and common law systems, and she is generally supportive of Scalia. Dworkin's effort is probably the best of the bunch, as he is the only one who offers a cogent, if unavailing, challenge to originalism. Nevertheless, Dworkin's view of constitutional interpretation collapses under its own weight during a debate over the Eighth Amendment: if, as he argues, the term "cruel and unusual" is to be defined anew by each generation, then what protection would it provide to those who happen to find themselves living during a future, more brutal generation? Answer: None. Dworkin would sap the Constitution of its protections by converting it into a pro-majoritarian document, which is contrary to the very purpose of a constitution.

The biggest disappointment is Tribe, an acolyte of the "Living Constitution" whose comment boils down to inane, conclusory criticisms of originalism as imperfect, a bunch of nonsense about "transtemporal[ity]" and constitutional passages being "launched upon a historic voyage of interpretation," and a convoluted vision of the Constitution as being made up of an expandable "periphery" and a "concrete core" of rights. This tripe is bad enough, but what causes Tribe, Barack Obama's constitutional law professor, to lose all credibility is that he expressly admits at one point that he actually has no interpretative philosophy of his own--even if his model were accepted as valid, he concedes he doesn't know how one could determine which constitutional rights are "aspirational" and capable of expansion over time, and which are stuck in the "concrete core." One can surmise that those rights which Tribe favors would be given the expansive, evolutionary interpretation, while those he disfavors would be given the narrow, static reading. What Tribe articulates is not a coherent jurisprudence to guide judges in interpreting the Constitution, but rather an invitation to create a wholly new one by judicial fiat--a government of men, not of laws. With abominable legal instruction like this, it is unsurprising that Obama picks his nominees on the basis of decidedly non-judicial qualities like "empathy."

The mediocre commentaries notwithstanding, this is an immensely valuable book for the extended glimpse it provides into the mind and jurisprudence of one of the most important jurists ever to sit on the Supreme Court. Even if Scalia is unable to win your over, he will challenge your views with such force that you will inevitably be left with a deeper understanding of the Constitution. One could only imagine how much better off this nation, its court system, and its Constitution would be had people like Obama and Sotomayor been forced to read this book during their formative law school years. A MATTER OF INTERPRETATION should be required reading for any prospective law student or member of the bar.

درباره نویسنده

درباره نویسنده

اَنتونین گرگوری اسکالیا (انگلیسی: Antonin Gregory Scalia؛; متولد ۱۱ مارس ۱۹۳۶–۱۳ فوریه ۲۰۱۶) از قضات دستیار دیوان عالی ایالات متحده آمریکا از سال ۱۹۸۶ تا زمان مرگش در سال ۲۰۱۶ بود.

اَنتونین گرگوری اسکالیا (انگلیسی: Antonin Gregory Scalia؛; متولد ۱۱ مارس ۱۹۳۶–۱۳ فوریه ۲۰۱۶) از قضات دستیار دیوان عالی ایالات متحده آمریکا از سال ۱۹۸۶ تا زمان مرگش در سال ۲۰۱۶ بود.

این کتاب رو مطالعه کردید؟ نظر شما چیست؟

این کتاب رو مطالعه کردید؟ نظر شما چیست؟